Life is so random.

In early 1992, I called the Philadelphia Inquirer to ask about their summer internship program. I had missed the deadline for applications by a few days, the person on the phone told me. But she added that the deadline for applications at the Philadelphia Daily News was in a few days. They were in the same building, she said, which confused me – two competing newspapers owned by the same company, in the same building?

What’s the difference between the two papers, I asked?

“At the Inquirer,” she offered, “we win Pulitzers.“

That summer, I joined the Philadelphia Daily News as a photographer in the Knight Ridder Minority Internship Program.

During the program orientation, I remember one of the city desk editors talking to the assembled interns, most of whom were Black, and she said, “As people of color, we have a responsibility to make sure other people of color are fairly represented in the media.”

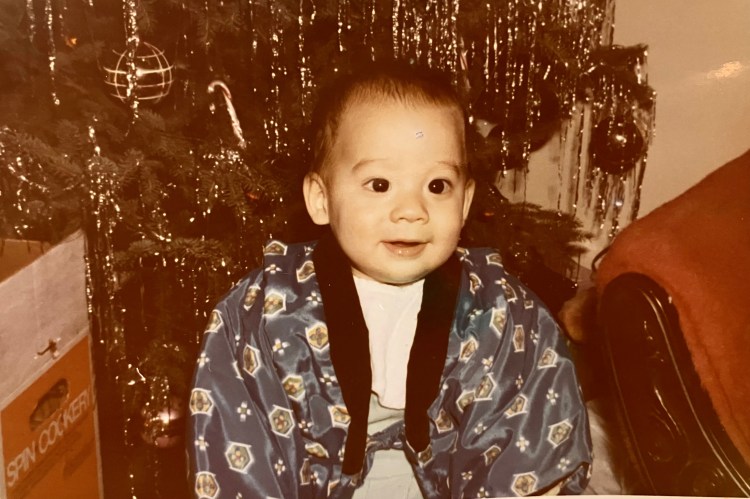

I felt guilty at first, like I didn’t belong in that meeting. I’m half-Japanese and half-white, and racially ambiguous at best (that’s me pictured above, circa 1984, in the blue fake-Members Only jacket). For most of my life, I had dark black hair and olive skin, leaving a lot of people asking me, “Where are you from? Like, where are you from from?”

Even now, with my salt-and-pepper hair, people make assumptions and speak Spanish to me.

The city desk editor’s comments that day hit me like a ton of bricks. All of the sudden, I realized I was part of something bigger, an actual melting pot, a society of diverse people.

I grew up in Delaware in the 1970s and 1980s, and there were very few Asian folks in the region. My elementary school pictures have almost entirely white faces. I was bussed downtown for 4th grade and finally started seeing other complexions. That was the norm for the rest of my primary education. But even with that forced integration, the diversity was almost always Black and white.

In high school, I could count the Asian students on one hand.

As a latchkey kid, it was easy to disengage, to find comfort after school in Doritos and Star Blazers, and baseball practice in the spring.

Not fitting into either category and being mocked by all (as per GenX rules) was just normal. Whatever, you know?

The summer I spent in Philadelphia as an intern was amazing.

It was a period of transition for Philadelphia, which was out of money, leaving municipal workers threatening to strike. The crack era had decimated parts of the city. The murder rate was consistent but more deaths were by guns, largely because there was massive competition for the city’s open air drug markets.

The new mayor, Ed Rendell, acted as a cheerleader. Presidential candidates came through town. Jerome Brown died in a car crash. A home in Philadelphia won top honors as the most cockroach-infested house in the country in a contest sponsored by a pesticide company.

I visually documented all of that.

By the end of that summer, I had a professional-looking portfolio. It wasn’t just student newspaper stuff anymore. I had documented the life of a major metropolitan area during a strange and busy time. That helped me land freelance work at the Baltimore Sun and Associated Press when I returned for my senior year of college. That portfolio helped me land an internship at the Ft. Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel after graduation. Shoot, it also got me an offer for an internship at the New York Times but I had already accepted the Florida gig, so I turned them down.

I have no doubt I would have found success in life no matter what but that minority internship program – that small piece of affirmative action, opened up the world to me.

My time as an intern at the Daily News revealed that I had some talent, I was enthusiastic and I worked hard. The editors liked me, and they asked me to come back after graduation.

About a year later, I returned to the paper as a staff photographer. I spent the next 12 years there, shooting images and writing stories. I learned so much about the world in that time, as I was exposed to so much. A journalist gets to briefly live other people’s lives, and I experienced the highs and lows, for better and worse.

I’ll never forget the sound of the wailing family in Fairhill after a 10-year old was shot while sitting in a van outside a corner shop in North Philadelphia. My job was to learn about the life that was lost. Most of the family spoke only Spanish. I had to wait patiently for an English-speaking relative. It was heartbreaking.

But I also documented spring training baseball and arena concerts, as well as the pet-of-the-week, political press conferences, and all the other minutia of daily life in the city.

It was real. I feel like I earned a doctorate in Philadelphia Studies.

This knowledge helped me land a full-time teaching gig at Temple University, and my experiences teaching at Temple for 17 years helped me land my current gig at Columbia University.

Every day, I talk to faculty members whose parents were academics and medical doctors. My mother waited tables for almost 50 years. My father sold cars when I was a kid. My grandfather paved roads all his working life. My grandmother drove a bus. They had an outhouse until the 1950s.

I wonder where my kid will end up?

One time, a reporter at the Daily News casually told me that I was a quota hire, implying that I only got the job because I helped pad the diversity stats. It was stated so nonchalantly, as if everyone knew that to be true.

I buried that shit at the time. I was having the time of my life. I didn’t let the pettiness get in the way.

(Fun fact: A decade or so later, I hired that person as an adjunct at Temple.)

On the opposite end of that spectrum, I was once offered a job at a legendary Midwest newspaper because an editor thought I was Black. My resume and portfolio had been passed along to him somehow, so he called me on the phone.

“We like to have a diverse staff,” the guy said. “We just lost one of our African American photographers and we’d like to fill that open position with another African American.”

I realized he saw that I had done a minority internship program. And with a name like George Miller, he just assumed I was Black.

It got really awkward when I responded with, “Um, I’m Japanese.”

I assume that being Japanese helped me get into the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University as a student back in the day. I don’t know for certain. I mean, I hope they saw my resume and saw that I was committed to the craft. But they also received my undergrad transcript, and I didn’t exactly have an Ivy League-worthy GPA. Maybe the essay I wrote about freelancing through college rather than studying for those econ and religion tests convinced them that I was driven and not just lazy?

Have I benefitted from affirmative action practices? No doubt. Did DEI efforts create a pathway for entry for me? They sure did.

Is that a bad thing? I don’t think so. While I don’t represent the people who were most historically oppressed in this country, I do represent a population of people who were not historically seen beyond stereotypes.

And whenever I got opportunities, I worked my ass off. I have always tried to do twice as much as required to combat any notion that I might not be worthy.

Now, my greatest desire, my most important task in life, is to make sure others have similar opportunities.

The images? All are copies of printed pics, most of which were taken using a Disc camera. The baby pic is me. Shoutout to Hanby Junior High School. Please enjoy my awkward years.

Incredible story. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike